Often have I stood on the plains of western Kansas and heard the voices of the past come to me on the incessant wind, whispers of lives that were spent between the great bowl of the sky and the unforgiving earth. They aren’t real voices, of course, but a product of my mind, a kind of auditory hallucination informed by history and sharpened by the vastness of the prairie.

Nowhere have I had this sensation stronger than at Fort Larned National Historic Site, along the old Santa Fe Trail in Pawnee County.

I’ve never stayed long at the fort because those voices give me the chills. The fort is a fine national historic site with excellent interpretive material, but my autonomous nervous system goes on alert. On this Indigenous Peoples’ Day weekend, I can’t help but think of the role the fort played in the pageant of brutality that was the West. It is a story of bad faith and broken treaties.

I don’t presume to speak for the actors in these events, whether they were First Peoples or white soldiers, nor do I condone the brutality practiced by either side, but the facts remind me of how uncomfortable it is sometimes to be an American.

And discomfort is useful in studying the past if we are to learn from it.

Stanley’s dispatches

The national historic site, six miles west of the city of Larned, has nine restored sandstone buildings, including barracks and arsenal, and is among the best-preserved forts of the period. At its peak, Fort Larned housed about 500 troops and provided administrative and material support to the Medicine Lodge Treaty of October 1867.

The fort’s link to the Medicine Lodge Treaty (which was actually three treaties) was made clear by a correspondent for the Missouri Democrat, a young reporter named Henry Morton Stanley who would later be remembered for uttering, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” He was dispatched to the fort and points south along with the seven-member Indian Peace Commission, and from the dispatches he left I suspect he may have heard voices, too.“Generations after generations have been swept away,” Stanley wrote in one story, “mingling their dust with the common mother, and leaving to their successors their traditions and usages, as well as their darkness and barbarism. The Indians of the present day hunt the buffalo and the antelope over this lone and level land, as freely as their ancestors, except where the white man has erected a fort.”

Stanley’s remarks about “darkness and barbarism” are a reflection of the bias of his time, but he could have said the same about the military and government officials in whose company he traveled. In 1864, the U.S. Army (over the objections and refusal of some officers and men to participate) had massacred 160 women and children at a Cheyenne and Arapaho encampment at Sand Creek in Colorado Territory. Before the slaughter, Chief Black Kettle had been flying an American flag from his tipi.

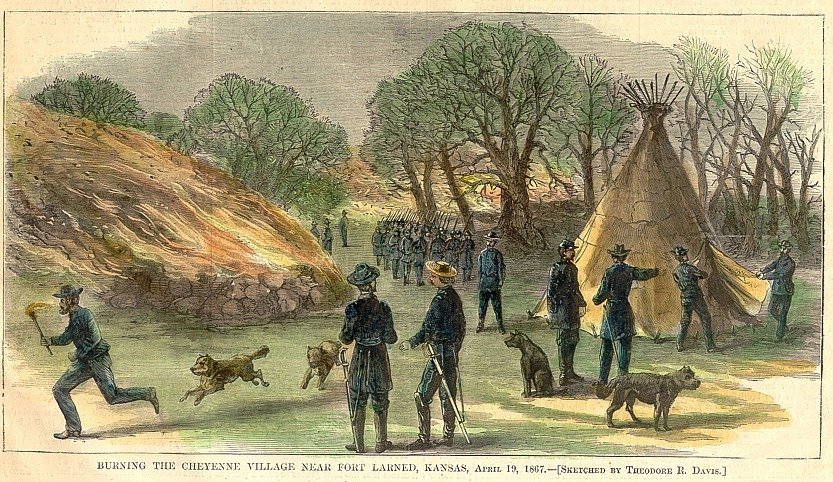

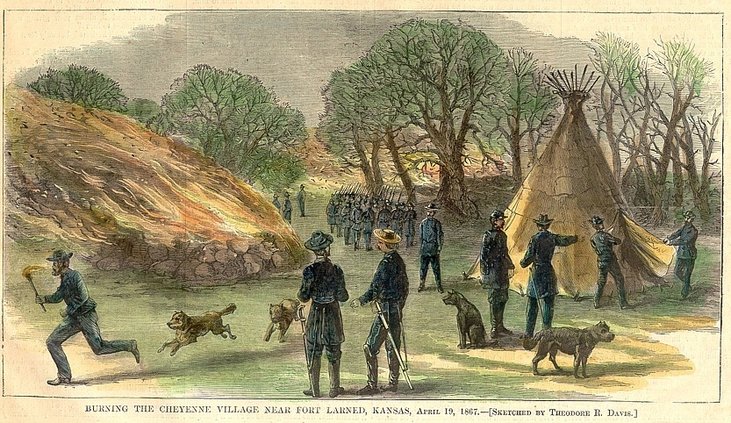

“After Sand Creek the Indians were at war everywhere, mostly on the Platte,” Stanley told his readers. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, a hero of Gettysburg, attempted to force the plains nations into submission. On Hancock’s orders, George Armstrong Custer burned a Cheyenne-Lakota village west of Fort Larned.

A series of fights followed, including one in which an entire detachment of cavalry was killed near present-day Goodland. By the end of the summer of 1867, Hancock was transferred to another command and a new plan came from Washington — diplomacy, because the fighting in the west was growing too expensive.

The Medicine Lodge treaties that followed were held at a sacred spot for the Kiowa and Cheyenne, on the Medicine Lodge River near the mouth of Elm Creek, about 100 miles south of Larned. The fort supplied the provisions for the council, including food for all of the former combatants.

It may have been one of the largest assemblies of First Peoples on the plains, with contemporary estimates ranging up to 15,000 individuals. The nations represented included the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche and Apache. Probably the most famous — and most feared by the whites — among the native people was Satanta, a Kiowa chief known for both his fighting skills and his soaring oratory.

The Indian Peace Commission was escorted to Medicine Lodge by 500 troops of the Seventh Cavalry, but George Armstrong Custer wasn’t among them — he had been court-martialed for being absent without leave and for ordering the shooting of deserters. His punishment was a year’s suspension without pay.

“We hope now that a better time has come,” Satanta said through an interpreter, according to a 1938 magazine piece recounting the event. “If all would talk and then do as they talk, the sun of peace would forever shine. We have warred against the white man, but never because it gave us pleasure. Before the day of apprehension came, no white man came to our village and went away hungry.”

Satanta said he was ready for peace.

The 1938 piece may be apocryphal, as I cannot readily find another source for it. There is nothing similar in Stanley’s dispatches. But it matches the spirit of what Satanta likely believed. In an earlier speech, before the peace council, Stanley had reported that the chief was done with fighting. “There are no longer any buffaloes around here,” Satanta said, “nor anything we can kill to live on; but I am striving for peace now.”

From the plains to the reservations

From Oct. 21 to 29, 1867, three separate treaties were signed at Medicine Lodge that collectively reduced the area set aside for the plains nations by 60,000 square miles. In exchange, the First Peoples nations were given reservations in the southwestern corner of Oklahoma and allowances for food, clothing and other provisions.

The Indian Peace Commission would continue through 1868, negotiating other treaties with northern plains nations, and in time would deliver a report to a Congress that was still struggling to define its relationship to America’s indigenous peoples. It took until July 1868 for the Senate to ratify the treaties, and some details that were understood during the October meetings were dropped in legislation, including a promise there would be sufficient buffalo on the new reservations.

Also, the U.S. government misunderstood the collective nature of political power among the plains tribes. While a chief might affix a signature to a treaty, it was not understood as necessarily binding all members of his nation to the document. While the treaties called for three-quarters of the males of a tribe to ratify them, that does not appear to have happened.

Not long after the peace commission’s gifts of beads, buttons, knives, cloth and pistols had been taken home, discontent was again brewing among the plains nations. Reservation life, restricted geographically and tied to government allotments of food and supplies, was an unsatisfactory substitute for the nomadic culture the plains nations had previously known.

Brutal raids into the old hunting grounds of western Kansas resumed.

By 1871, Satanta was attacking wagon trains in Texas, was eventually captured, and became among the first Native American leaders to be tried in a U.S. court. After serving a couple of years in prison, he was released but violated his parole by being present at the Second Battle of Adobe Walls. He was captured and sentenced to life in prison at Huntsville, Texas. He died at age 62 of a fall from a high window of the prison’s hospital on Oct. 11, 1878.

Another broken treaty

The peace commission was the U.S. government’s last attempt to negotiate a peaceful settlement with the First Peoples, according to the National Archives. While the goal was peace, the result was the opposite. In its final report, the commission recommended that the Bureau of Indian Affairs should be transferred from the Interior Department to the Department of War.

By 1868, Custer had served his punishment and had been summoned to active duty to participate in a new campaign against the plains nations. In November he attacked a Southern Cheyenne camp on the banks of the Washita River in Oklahoma, and killed 50, including Chief Black Kettle, who had been at Sand Creek and was a signatory at Medicine Lodge. Fifty-three women and children were taken prisoner by the Seventh Cavalry.

In 1874, Custer led an Army expedition to the Black Hills, in which gold was found. Faced with an influx of fortune hunters onto land that had been given to the Sioux, the government violated the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, a deal that had been brokered by the same Indian Peace Commission that had been at Medicine Lodge. Settlers poured in, and the northern plains nations resisted.

Custer would meet his end at the Battle of the Greasy Grass in the Little Bighorn Valley of Montana Territory. On June 25, 1867, he led five companies of the Seventh Cavalry against a village he had badly underestimated the size of. Custer and 267 of his command would be killed by the combined forces of thousands of Lakota, Dakota, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors.

‘An ignorant and

dependent race’

Despite winning the biggest battle against a celebrated enemy, the plains nations could not withstand increased pressure from the U.S. military and white settlement. The decades-long conflict ended Dec. 29, 1890, at Wounded Knee, Dakota Territory, where 300 Lakota people were massacred by the U.S. Army in a campaign to suppress the Ghost Dance religion. Based on the visions of a Paiute holy man called Wovoka, followers believed the buffalo and the ghosts of ancestors would return to earth — and the whites would be swallowed up — by ritual dancing.

While the fighting had ended with Wounded Knee, the battle over the Medicine Lodge and other treaties continued in the courts. From the reservation in Oklahoma, Kiowa leader Lone Wolf sued Secretary of the Interior E.A. Hitchcock in a case which boiled down to a single question: Could Congress unilaterally break treaties? The answer from the Supreme Court, in 1903, was a unanimous yes.

“These Indian tribes are wards of the nations,” the decision said, consisting of weak and helpless communities wholly dependent on the federal government. The court presumed that Congress would be guided in its treatment of “an ignorant and dependent race” by Christian values.

Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock was the rule of law for most of the Twentieth Century. It granted Congress plenary power over the plains nations, meaning that its power was absolute, with no review or limitations. Although reversed in large part by United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians in 1980, the shadow of Lone Wolf continues to leave a foul taste in our collective mouths, a bad decision that has been compared by historians to the Dred Scott decision.

“The young Plains culture of the Kiowas withered and died like grass that is burned in the prairie wind,” wrote N. Scott Momaday in his 1969 book, “The Way to Rainy Mountain.” Momaday is a Kiowa author and a descendant of Lone Wolf, and his novel is about his ancestors’ path to the reservation. “There came a day like destiny; in every direction, as far as the eye could see, carrion lay out in the land.”

It is time for Kansas to adopt Indigenous Peoples’ Day as a state holiday. About a dozen states have already done so, including Oklahoma. Both the cities of Wichita and Lawrence celebrate it, although the Kansas Legislature was unmoved after hearings in 2019 and 2021. But considering our state’s pivotal role in the war against the plains nations, and the many contributions of Kansans of indigenous heritage, it would be a small but corrective move toward celebrating a culture we nearly destroyed.

Listen to the voices on the wind.

By Max McCoy. He is an award-winning author and journalist. Through its opinion section, the Kansas Reflector works to amplify the voices of people who are affected by public policies or excluded from public debate. Visit kansasreflector.com.